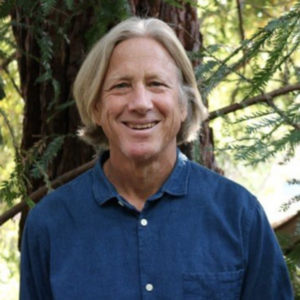

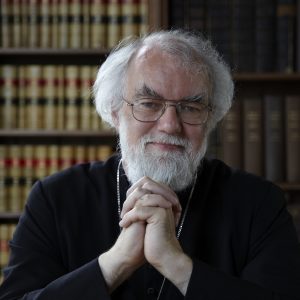

Dr Alex Curmi is a psychiatrist and psychotherapist who also hosts The Thinking Mind podcast. Alex is a gifted communicator, having delivered a TED talk and written articles for the Guardian newspaper.

Kenny Primrose: 2:35

Dr. Alex Curmi, it’s such a pleasure to have you on the podcast. Thank you very much for joining me. Thank you, Kenya. Thank you for inviting me. Um, there’s, you know, as you know, the theme of the podcast is to explore a question that an influential thinker, someone like yourself, thinks we should be asking. And we will absolutely come to that question. But I wondered if we might begin by hearing a little bit about you. You’re a psychiatrist, you’re also a psychotherapist, you also host the Thinking Mind podcast and do some writing and some speaking. So I wonder if you could tell us your journey. What have been the themes that have guided you to where you are? Yeah, so I think the biggest theme that’s guided me, which I’m happy that I let myself be guided by this theme, was I let myself be followed by my interests without any one decision needing to be the best ultimate decision. Around 18 or 19, I had to decide what I wanted to study at university. And I liked biology and chemistry and science, and I liked the idea of understanding the physiology of the human body, so I chose medicine. It seemed like a logical route. But then when I started medical school, in the middle of medical school, I started to intuit pretty quickly that maybe a more conventional medical career, as a GP or internal medicine specialist, probably wasn’t going to be for me. Within medical school, I then found psychiatry. So immediately I’m really fascinated by psychiatry, the dark aspects of the human mind, what can go wrong for people mentally, behaviorally, etc. So I decided to specialize in psychiatry after doing two or three years of general medicine and surgery and geriatrics. I then started training in psychiatry. I like psychiatry, but there were certain aspects of psychiatry which weren’t fully satisfying to me. And then I discovered psychotherapy. When you train as a psychiatrist, you get to experience a bit of psychotherapy. So you get to try out cognitive behavior therapy with a patient and psychodynamic therapy with a patient. And then I really fell in love with that kind of things. Alongside my psychiatric training, I started a psychotherapy training program, which I’m about to finish in six to nine months. In parallel to all of that, I love learning and teaching. And I felt there should be better online resources for people to learn about mental health, psychology, and self-development. Roughly at the same time that I started psychotherapy training, I started a podcast, which has now become a weekly podcast where I talk to expert guests, or sometimes just riff by myself on a variety of topics. That’s been super fun. So that’s been three prongs of my career mostly have been psychiatry, psychotherapy, and now podcasting and some speaking and writing. But it’s all centered around my interests, which is the mind, behavior, why people do what they do, what steps can people take to live a higher quality of life. These are the things I’m interested in. And I’ve been fortunate that I’ve been able to build a career on those things. Okay, fascinating. Thank you. And do you find that the psychiatry is obviously medically based? Psychotherapy is much more talk therapy. Are they comfortable bedfellows for you? Do you use kind of both interchangeably? That’s a good question. I think for many people, they’re not comfortable bedfellows. But I think for me they are, and that’s because I’m comfortable with the tension that can arise between them. In many ways, a psychiatric approach can complement a psychotherapeutic approach, but that doesn’t mean there are differences and tensions that arise between them. For example, if someone presented with symptoms like intrusive thoughts, and as a result, they felt compelled to do certain things through a psychiatric lens, those would be symptoms, symptoms of a disorder, possibly something like OCD. Those are symptoms or misfirings of your brain worth treating and kind of almost getting rid of, might be a crude way to put it. Whereas if you view the same set of issues psychotherapeutically, it’d say, no, actually, these are coping strategies. They’re coping strategies that a person has developed to deal with uncertainty. Perhaps they had a very unstable or inconsistent childhood environment. And this was their brain’s best attempt to deal with that uncertainty and instability. Now that they’re an adult, the same set of coping strategies isn’t working so well. So we have to help the patient become more aware of that and hopefully develop newer, better coping strategies. So that’s one example of the way a psychiatric view and a psychotherapeutic view can be in conflict with each other. If you want to be in both, you just have to be okay with that conflict and to know sometimes one approach might be better than another, more appropriate. Sometimes a patient might prefer one approach over another. You might have one patient who has that same set of problems I described, and they’re like, I don’t want to learn about myself. I don’t really want to go into my childhood. I would like you to give me some skills and strategies and potentially some medication to help make my mental life easier. And who am I as a professional to say that’s an inappropriate way of dealing with it? Someone else might be like, no, I don’t really want to take medication. I want to get to the root cause of this, and therefore a psychotherapeutic approach might be more appropriate. There’s all sorts of reasons why one might be more appropriate than the other. So the way I think about it is just try and figure out what view is most appropriate at that time for that person. Even within psychotherapy, there’s many different schools of thought, and I’m familiar with a few of them. Even in that world, I have to decide is a cognitive behavioral approach better or is a psychodynamic way of thinking about this patient more appropriate? And so a lot of my career has been trying to figure out all of these different lenses you can take on human problems, and then being comfortable deploying different lenses in different situations at different times. So that’s kind of how I think about it. Okay, really interesting. And actually, not a bad segue into the question that we’re going to explore. Some of the things that surface in psychiatry will always have surfaced, or psychotherapy, it will be attachment issues and things like that. But as we both know, we’ve been living through a fairly tumultuous time. The things around us are changing, and that is showing up in your clinical work, the way we’re affected by particularly technology. I wonder if we might use that as a step into what your question is. Alex, what is the question that you think we should be asking ourselves and exploring at this current moment? Firstly, I’d like to say I love your format. I love centering an episode around the question like that. I think it’s really good. The question I landed on was, and it’s been something I’ve been thinking and writing about quite a lot. In a world where technology has been quite disruptive psychologically for a lot of people, how do we prepare for an increasingly technological future? Because we live in a technological world, but we’re not at the end of history. This is not the end of the line. Changes continue to intensify every single day. So the question is, how do we go preparing for that? It’s a great question. And it’s one that I think is it’s definitely in the back of my mind as a parent, I’m thinking, how do I help my children prepare for a future which is in so many ways unknown? And what I can see coming doesn’t fill me with hope. Actually, it terrifies me in lots of ways. Let’s take the first part of what you just said in a world where technology’s already been so psychologically disruptive. What’s bubbling up for you there? What is the technology that that you see surfacing psychologically as trouble? Well, to frame this, I’ve been doing a bit of research about this. We have spent 90, something like 96, 97% of human history with been nomadic hunter-gatherers, possibly more, but let’s say it’s around 96-97%. So most of human history, we’ve been living in a very low technology environment. And so we’ve evolved to deal primarily with a low technology environment, small bands of people working together constantly, very much immersed in nature, immersed in dynamic problem solving, solving problems which are very concrete for most of our history. Where do we get food? Where do we get water? How do we avoid a predator? How do we survive this next weather event or this next famine? But over the past few, you know, thousand years, again, very, very small sample of human history. We’ve developed agriculture, civilization, and now, most recently, in the past couple of hundred years, the Industrial Revolution, and now in the past like 20, 30 years, the internet, smartphones, in the past three years, you know, large language models going mainstream. It’s getting really intense. I think you can make a strong argument that the human brain isn’t evolved to deal with this level of technology. One way I like to put it is we’re victims of our own success. Something that makes us human is our strong desire to innovate. The fact that we can imagine a better future than we have. A dog can’t appraise the present, figure out what’s wrong with it, and then imagine a better future. But a human can do all of those things. So we create lots of technologies that help us get that better future. We think, wouldn’t it be nice to have control over hot water, you know, rather than just having to rely on a hot spring? Wouldn’t it be nice to have water that’s hot, that’s piped directly into our cave? At some point in human history, someone saw this as a problem and imagined we could be different, and now it is different. The problem is that these very seductive innovations and technologies don’t just add to our lives in a static way and make our lives better. A lot of technology is very seductive up front, but surreptitiously very depleting. So it gives us a lot on the front end, but it takes us in a kind of deceptive way. So an example might be because we have cars, we don’t have to walk so much. That’s amazing. That’s so convenient. Doesn’t it feel good when you’re tired to be able to just call an Uber and have someone drive you to where you’re going? You don’t even have to speak to them now. You can just click a few buttons and that’ll happen. But the ability to walk long distances is very important for human health. So up front, we get this convenient technology that feels really good emotionally, makes us feel good because we feel like we’re saving energy. But over the long term, if you always drive, you always get driven places, but you never walk, that’s going to have a serious impact on your health. It truly is the case that this is impacting people’s lives. So, for example, we know older people, as a result of not walking, are much frailer. Because of that frailty, they’re much more likely to fall, break their hip. As a result of breaking their hip, going into hospital, getting a chest infection. This is a very common reason why people actually die. So it’s not trivial by any means. And that’s just one example of the way that technology can make a world that’s very comfortable, but then kind of rob us of our most human qualities. So that’s an example. Great example. There’s so much that came to mind when you were speaking there. I had on the podcast a while ago Anna Lemke, the psychiatrist, who uh her her focus is dopamine, and she says we evolved in a world of scarcity and now live in one of abundance. And I think we’ve got to in some way go against our biology. As you say, we’re into energy conservation, but this is to a fault when your muscles atrophy and you don’t bump into people on the way to the shop, the social connection, and so on. I think there’s also something there on convenience technology robbing us of any sense of mastery. Uh, Albert Borgman, the philosopher, talks about central heating. It’s the flick of a switch on a thermostat. There’s no sense of engagement or mastery in that, as opposed to building a fire, which you you have to tend, you would it ends up being kind of a social as well as a physical thing. What are the psychological ones that you’re regularly seeing? Living in a world of such kind of before we even get into large language models and things like that. I think the psychological ones are ones that you’ve already kind of hinted at. I think people are feeling a lot less confident in themselves, a lot less confident that they can overcome difficulties, intolerant to uncertainty, because in many ways, technology, I don’t think it provides certainty, but it provides the illusion of certainty a lot of the time. I think it robs people of the experience of going through something uncomfortable in order to make themselves stronger as a result. I think it also robs people of sensitivity to joy and to kind of natural experiences. So, an example might be someone who is addicted to video games, and I don’t want to fully knock video games, many people play video games and have a good relationship with them, but if you’re addicted to video games, many people report that it’s very overstimulating, and so does kind of a numbing effect, where if you spend all day on video games or even something like TikTok, you might be less able to appreciate the sunset. Those technologies are acting on the same kind of reward systems that might respond to something in the natural environment. The way biology works is there’s often a balance. If you over-stimulate, there has to be a period of recovery. Over-stimulating your brain with technology makes you much less able to appreciate things that happen naturally. And other example is pornography, where people who are addicted to pornography will commonly report it’s much harder to get aroused when they’re with their partner, because their partner, even though they’re a real person, can’t compete with the ridiculous variety of images and the intensity that one can experience with pornography. Drugs are another example where if you use cocaine, that causes something like a thousand percent increase in dopamine release between nerve cells over baseline. If you do a lot of cocaine regularly, you’re gonna find it a lot harder to get reward and motivation from, say, your job or getting a promotion. These are a few of the psychological consequences. Also, I mean, this is less related to technology itself, but more our culture, our culture has stopped talking about I think morality, character building, notions of integrity. I think, and I and I think we’re really feeling the psychological effects of that as well. So those are a few examples. So, I mean, social skills one more example, social skills, you know, because it’s so easy to spend so much time alone because of technology. A lot of people appear to be finding, especially younger people, it’s harder to form and maintain relationships, which is so important. So those are a few examples. Really helpful, and I could kind of structure where we go next. What comes to mind is the mental health crisis, the current meaning crisis, as it’s been called. This seems closely related to an absence of social connection, but also, as you say, morality and character and a sense of struggle. There’s something about struggle that’s kind of constitutive of flourishing. You mentioned uh well, let me let me relay a few things and maybe we can explore them. Lack of confidence. I I’d love to hear a bit more about why you think that’s the case. I think it’s tied to the fact that it’s easier to not voluntarily expose yourself to difficult situations and overcome them. Because I think that’s the essence of confidence. There’s a really good book about confidence written by the same author who wrote The Winner Effect, and he defines confidence as this sense that you can do something and you will do something. So I’m confident that I can do this podcast and have this conversation with you because I know I can, I know I have the capability, and I know I will, I have the willpower. But this didn’t happen overnight, right? The reason I feel confident doing a podcast with you is because I’ve done around 150 to 200 podcasts in the past. So it’s not like I started from a place of totally not being able to do it, and then all of a sudden I can do it. It’s a gradual process of trial and error, of being very comfortable with failure, comfortable with making a mistake in a public setting, people thinking less of me because they might see me making a mistake in public or something like that. So I think confidence ultimately is arriving at this ability where you know you can do it because you have proof. I have the proof in my memories of all the podcasts I’ve done. But to get to that point, you have to be super comfortable, you have to be super comfortable with discomfort. You have to be comfortable figuring out, okay, where am I definitely competent? And then maybe going outside that a little bit, pushing the edge. In psychology, this is called the zone of proximal development. You do that again and again over months and years, and you get results from the world that tell you you’re on the right track. You also get results from the world that tell you you’re on the wrong track, and maybe you should do something differently. Hopefully, you pay attention to that feedback from the world, and that informs how you go about whatever activity you’re going about. So if an audience member gives me some constructive feedback, I might take that into account the next time I do a podcast. You do that over years, and then you arrive at a position of confidence. But increasingly it feels like there’s a culture of you know, not wanting to fail, not wanting to push yourself in a position of discomfort at all. A lot of the discomfort that people face in modern society is discomfort that’s thrust upon them as opposed to voluntarily sought out, and that has a very different psychological dynamic. I think when discomfort is forced upon us, we tend to feel oppressed and restricted. Like, for example, if how housing prices skyrocket and you can’t afford a house, that feels like oppression, that doesn’t feel like a self-development activity, and rightly so, it’s difficult. But conversely, if you find something uncomfortable and you chase it, you voluntarily go into it. Psychical research would suggest that makes you a stronger, more resilient person. So to the extent that none of this is encouraged and the culture continues to regress away from that, people are gonna be feeling a lot less confident, I think. Yeah, it’s a really important point, especially I think when you’re working with young people, uh developing an inner locus of control, a sense of agency, and the you know, this a the this sense that you’re able to do something, when that is replaced by helicopter parenting and never being in risky situations, you never develop a sense of being able. There’s a kind of feebleness of mind that comes with it. Jonathan Hyatt argues that we’ve gone from physical safetyism to psychological safetyism, hence cancel culture, trigger warnings, that kind of thing. Because there’s this kind of phobia of discomfort that is not just perceived as real because you’ve never experienced it. I wonder if the same experience is true for you. When I began a podcast and began to write a bit more, and I suppose do something that felt a bit daring. There’s something a little bit daring about putting your voice out there. I’ve had a tremendous feedback of feelings of agency and confidence. It’s not that it’s always gone well or that I’ve triumphed, it’s just that you try this thing out and you realize that the ground doesn’t open up beneath you, and you can try it again and get better at it. Having a podcast is one of the things that’s single-handedly improved my confidence almost more than anything else. And I’ve worked in really high stress environments on AEs and psychiatric wards. Obviously, those also help my confidence. But there’s something about the podcast in that it’s totally self-driven. I’m not part of a system or an institution. I had to do it all, you have to do it all yourself. You’re in charge, you’re the boss. That really, really improves your confidence because you start to be able to rely on your own ability to make things happen in the world rather than just plugging into an existing system. You can plug into an existing system and learn great skills and confidence. But there’s something about having something that’s yours that could be a podcast or a business or anything you could think of that engenders that sense of agency, that sense of I can exert an effect on the world, you know, I can make my desires into some form of reality, even if you’re not wildly successful, you feel like you’re just a little bit more grounded in reality because really you are, if you have something you want to do and try your best, you are less grounded in fantasy and more grounded in reality. So, for example, if you’re like the prototypical adolescent in the parents’ basement who thinks, you know, I could write an amazing novel, I just don’t feel like it, or I don’t think it’s worth writing an amazing novel, you’re in a fantasy world. But you’re fantasizing about this amazing novel you’re gonna write, and you’re not learning anything, and you’re not really grounded in reality. As soon as you set pen to paper and start to produce something, maybe you write a chapter or a short story, or maybe eventually you do write that novel, and then God forbid you show it to someone, to your friend, or a teacher, or your literary agent, all of those actions put you further into reality and allow you the chance to get feedback from reality so you actually know where you’re at, you know what’s going on. But while that stuff’s all in your head, you’re just adrift in a fantasy world, and that’s I worry about that a lot. In McGillchrist, I think you had on your show, yeah, he uses the word simulacrim, which maybe is the best word, is that a lot of people live in a simulated, almost reality that’s not quite reality. Yeah, it’s fascinating. I wonder whether you noticed a difference in the generations that come into your clinic, uh, as in the problems that they bring to you notice that people who are middle-aged have developed agency because of the times they grew up in, and those of a younger generation much less so. Is that something that surfaces just because of the formative years and the technology that’s around when you’re growing through that? I think every generation will have its kind of pros and cons. What I do see with younger people, that’s an advantage is I think a lot of young people are more aware of the possibility of mental health problems, how to handle them proactively. That actually self-care, you can think about self-care in a corny Instagram way, but I actually think self-care is really important. A lot of young people are thinking about psychological and personal development, that’s really good. But I do think maybe the downside of being in the younger generation is there does seem to be an increasing sense of safetyism, of overreach of psychiatric concepts like diagnosis and concepts like trauma. This is something that I have discussed on my podcast. And so it’s a mixed bag. But yeah, I do see some of those trends we’ve alluded to so far. One thing that I have heard anecdotally from a lot of my friends in the working world is that when they work with younger people, say people from Gen Z, it seems like a lot of them have problems with confidence, anxiety, social skills. But then there’s a small minority of people from Gen Z who are the most competent you’ll ever meet. So these seem, and this might lead into how we might think about these difficulties and what a person can practically do. But there does seem to be a small minority of people from the younger generations that are actually able to take advantage of all the pros of technology and actually be hyper-competent and really reliable and things like that. It’s interesting this irony that we’ve never had such power and such reach, and yet it’s kind of crippled a lot of people in terms of what they feel able to do. You mentioned that there’s an intolerance towards uncertainty, and I take from that that technology gives the illusion of control, yet we still live in a world which is uncontrollable. Right. Uncertainty has always been a problem. I’m sure the people around in 1905 couldn’t have predicted an a basically apocalyptic world war that started around 1914, and then not only that, but then the same thing would repeat itself with like 10 times the casualties 20 years later. There’s no way they could have uh uh predicted that, and there’s no way we’re gonna be able to accurately predict now what’s gonna happen in the next 20 or 30 years. We can have some ideas and maybe some principles, we’re probably going to be wrong. And so I think tolerance to uncertainty is necessary for everyone, and I also think it’s a hallmark of psychological maturity, and what you find is when people are unable to tolerate uncertainty, usually different psychological problems develop. So, one is like obsessive-compulsive type patterns are a really common response to not being able to tolerate uncertainty. As I mentioned in my example at the beginning, someone in a kind of unstable childhood environment may develop these tendencies to cope. Perfectly rational response by the brain, kind of a beautiful response in a lot of ways, that the mind is trying to create these systems and thought patterns to give this sense of predictability. But we know it’s kind of an illusion, we know it’s kind of not real. And technology feeds into this. We can use air conditioners to precisely control the temperature that we live in. We can contact Amazon and have something made in a factory in a different country, delivered to our homes the next day. And so this gives us this profound sense of control of our reality, but then things happen we would never predict. COVID was a good example. For many people who experienced COVID had never experienced anything like it, where the rug is really pulled out from under them in a way that’s never happened before. It was really interesting to watch a lot of people’s response to COVID and lockdowns. A lot of people were responding like it was bad customer service. Like, what do you mean? Well, I just can’t leave my house. This is outrageous. But to people who might have lived through World War I or World War II, this might have been business as usual. Every so often something cataclysmic happens, which changes the way we live. Radically and you kind of have to roll with the punches. But I think this is new for a lot of people, but it shouldn’t be. I think we should do our best to uh inoculate ourselves to uncertainty. And how do we do that? So I think you’re right to point the finger at technology. Oliver Berkman’s got this nice observation that you um you know it’s somehow more frustrating to wait two minutes for something to cook in the microwave than it is to wait two hours for something to cook in the oven. It’s this sense that we have these godlike powers, and if it’s that quick, it should be quicker than that. There’s a kind of sense of entitlement that comes with the powers we have. So, how do you coach yourself into a place where uncertainty becomes a tolerable reality? One thing I’ve noticed with my mind, and I I think a lot of people will be able to relate to this, is I try and anticipate future problems and all of the different variables that might be associated with those problems, and then I try and account for them and solve for them in that moment. This is normally 3 a.m. when I’m trying to sleep. I think, okay, so if this particular question pops up in the exam, I’ll be able to deal with it this way and that way. And if the next exam I take after that is more focused on these topics, this is how I prepare. Your brain is constantly trying to account for any number of different problems that could occur in the future and plan for them. That is intolerance to uncertainty. That is my way of not being able to recognize that a situation is going to occur in the future and I’m just gonna have to handle it as it comes up. For example, another example might be you might buy a house and the plumbing might go, or the electricity might go, or you might have to change the boiler. And you think, if this happens, I’ll do that. If that happens, I’ll do that. Something I’ve tried to do instead, which I have found really helpful, is to develop what I call trust in my future self. I know there’s a limited amount of actions I should take now if I’m buying a house. I should definitely have a surveyor, look at it, and make sure it’s sound and make sure there’s nothing overtly wrong with it. But the amount of actions I can take in the present are limited. I have to understand at a deep level that things will pop up that I’m not able to predict, and I have to trust that my future self can handle it. I can look back at the evidence of things I’ve done before and other problems I’ve handled and be like, okay, I am someone who can solve problems. I don’t have to anticipate any problem I’m going to account I’m going to run into months or years in advance. When I encounter unpredictable problems in the future, I will be able to handle it. And I found that personally as a very relaxing kind of mindset. And to really have a to develop a high-resolution sense of what is in my control and what’s outside of my control and what’s realistically, what dials can I move and which ones I can’t. Yeah, it’s very much the kind of stoic or serenity prayer, like give me the wisdom to know the difference between what I can and what I can’t. It seems intimately related to a lack of confidence. If we trust that we’ve got agency to deal with what unknown beast is around the corner, then we’re not going to be anxious. But if you feel this lack of confidence to deal with the situation, then you try and game it. So this podcast is a good example. If I was less experienced in podcasting, I could have tried to anticipate any possible question you could ask me. I could have tried to memorize a script of different answers. Because if I don’t memorize it, I might flab a word or say something stupid or use an example that’s not particularly appropriate. But that doesn’t really work because there’s too many different things that could come up. There’s too much unpredictability. So instead, what I did was I prepared, I wrote notes, I have a rough idea of things I could talk about and answers I could provide. But I’m also going to have the courage to let myself speak and let myself think out loud, let the chips fall where they may. It won’t be perfect. But perfection is neither attainable nor desirable, I think. 100%. I think of there’s a German sociologist called Harmart Rosa who talks about the uncontrollability of the world and our desire to control it. He says what we lose when we try and control things too much, like a conversation. There’s a kind of turgidness that comes with it. And we the his word, at least the English translation, is resonance. You lose any sense of resonance by controlling. I I wonder if this is a nice segue into your other point, which I love, that we’ve become insensitive to joy and experience. So I wonder if you could say something about how we’ve lost joy and experience in the way that we’re living with machines. I think it comes down to that dopamine balance that I’m sure Anna Lemke would have told you all about, which is the technologies are simply too stimulating and so natural life can’t really compete. I I don’t think. And I I don’t really see much of a way out of it other than to simply restrict your use of technology to a sensible level. I mean, I everyone uses technology, I’m not anti-technology per se, but I don’t really see a way out of it other than restricting your use of technology to a sane level, and then seeking what I would call maybe more natural adventures, spending time in nature, socializing with people in person, dating in person, not always meeting people online is another good example. Trying to do hands-on practical things in the world, starting your own business, things like that. Things which don’t rely on artificial technological stimulation purely. That’s the best way I’ve thought of to immerse yourself in life with all its ups and downs. Again, you know, joy isn’t just related to stimulation, but it’s also related to downs and things being difficult, you know. If you slog through some difficult months or years, but then ultimately make it through, you might find yourself a lot more sensitive to joy because you know how difficult life can be. If instead of like slogging through that difficulty, you kind of avoid it and numb yourself with things like technology, then I think that makes you less sensitive to joy. So that’s that’s a few of the ways I think about it. I’m currently reading Katherine Mannix’s book, What Matters in the End, about death and palliative care, and it’s just taking me apart. It’s it it in a in a kind of um sad but joyful way. These are feelings that we’re often living at a distance from. I think we unconsciously believe in modern society that opposites are very separate from each other, like life is very separate from death, happiness is very separate from sadness. But I don’t think that’s true. I think these things are kind of intimately related. An example might be when someone’s hand is developing in utero, at first it’s kind of paddle-shaped, and you don’t have fingers, but then a number of cells in that paddle die, and that death gives rise to the fingers that we rely on every day. Similarly, happiness and sadness, you know, if we can allow ourselves to tolerate and deal with sadness, let’s say someone dies and we’re grieving, if we can deal with that grief, that then opens up the possibility of happiness, re-establishing a connection with someone else. If we don’t face that grief, digest it, process it, we end up in this nether world where we’re too afraid to process this negative emotion, which makes us not able to receive any positive emotion. This is something you see a lot in psychotherapy, where clients may have repressed a lot and not dealt with a lot. That’s great in the short term to avoid dealing with too much negative emotion, but unfortunately, that also closes the door for more positive aspects of emotional life as well. A lot of clients will come to therapy saying, like, I find it difficult to form a new friendship, for example, because I can’t make myself emotionally available, and that would partly because of repression of other things. So, so I think what we think of as opposites are often very closely connected. Yeah, there’s a there’s a lovely quote by a physicist Max Planck. He said, I thought I might I might have the wrong person there, but it’s something like the opposite of a profound truth is not a falsehood, it’s another profound truth. Yeah, absolutely. There’s a truth here in that happiness can’t be pursued, it must ensue. We are busy pursuing what we think. You think of your you know, your Instagrammable life or whatever, and you you try and pursue that, and you’re almost certainly not going to arrive at it. Try and pursue something that actually feels meaningful and purposeful and will be hard, and you might well get happiness thrown in. But we’re tricked into thinking that we can suppress the negative stuff, distract ourselves from it, and follow hedonistic pleasure in the pursuit of a good life. Yeah, it’s a very seductive trick. Looking at people’s lives on Instagram and how great they seem, it works so well. We become convinced. I think it’s always worth comparing what you see on Instagram with what you see in real life. There might be people you know and you might see what their Instagram life looks like. I would encourage making an exercise of comparing someone’s Instagram life to the real life when you actually see them, socialize with them, and see them out up close. And that’s not necessarily to say, oh, that person’s lying or that person’s life is totally different up close to what it appears on Instagram, but it’s gonna be way more real. You’re gonna see stuff that’s way more beautiful and way more profound if you hang out with people in real life, but you’re also gonna see the wards and the flaws and the ups and downs, the stuff that would never make it to Instagram. So I really encourage a kind of proactive, direct comparison, what I see with my friends on Instagram versus what I see in real life, because it helps to dispel that illusion, you know. I remember a number of years ago, I had an idea for Lent. I thought I’m gonna take a and I don’t use social media much at all, really. But back then I did have an Instagram account that I updated, and I was gonna just take a photo of something charmless in my life. It was like a pile of dirty washing and one photo a day. I wanted this to take off and everybody to upload photos of how mundane and sometimes depressing and hard life could be, but it didn’t take off, probably because I don’t have very many followers and people don’t want to look at that. They were not drawn to it. One of the things you mentioned has me right on topic, really. I’m very interested in morality, values, virtues, character. Uh was the fact that you think this is lacking, and what comes to mind is the uh extraordinary success of people like Jordan Peterson who who’ve stepped into a vacuum there, and whatever you think of Jordan Peterson, he’s interesting for a reason. Now I wonder if part of that reason is we crave some bad character development, some sense of substance. What came to mind when you put that into the equation? I think we come from a past where life was very difficult in ways that it’s not difficult now, and that I think forces character building, and then also we had major religions, and religions provide so much, they provide a sense of meaning, a sense of what’s gonna happen in life metaphysically, a sense of an afterlife, but also a strong sense of moral guidance. Like, what’s the right way for a person to conduct themselves in life when faced with particular choices and dilemmas? How should someone proceed? Obviously, we’ve become a lot more secular in the modern West. And I say that not as an especially religious person, but increasingly as a person who recognizes the value that religion had, and perhaps that we’ve thrown there is an important baby that’s been thrown out with the bathwater. So, yeah, you can see examples of substitutions which have come into the culture all the time, which people do gravitate towards. I think people unconsciously, I mean, consciously in the West, we worship freedom. The West is all about I want to be able to do what I want to do with whomever I want. I want myself to be the sole architect of my identity, and I want to be able to change my identity immediately and quickly whenever I want. That’s what we’re thinking of consciously in the West. Unconsciously, we really crave boundaries and some guidance and some rules and some structure, organizations and people that come in to fill that void. I think Jordan Peterson is a good example, but anyone in the self-help, self-development world, I think a lot of it can be really positive. I think it’s good to have discussions about morality without necessarily being moralistic or without beating people over the head with it. I think a lot of people, especially younger people, think of morality as very archaic and disconnected from real objective results. So someone might think when they’re told dishonesty is bad, they might think they’re being told dishonesty is bad. In the abstract, good people are honest, so just be honest. But it’s not like that at all. Morality is really grounded in my view to results. I think honesty is actually a better strategy, which will get you better results, especially in the medium to long term. If you’re a business person, for example, if you’re a dishonest business person, you might be able to do really well because of your dishonesty in the short term. Think of someone like Jordan Minderwolf of Wall Street, he was running primarily on dishonesty and had a meteoric rise, but it’s totally unsustainable because you’re building a house of cards. Whereas more honest businessmen, someone like Warren Buffett, comes to mind, they can have a career that lasts not just five years, but decades upon decades. Morality isn’t this abstract thing we should think about to be better people in the abstract. Making mortions gets gets you better results, you know, better results in the world, in your relationships, in your career. And so I think it’s really important for us to be having conversations, and I welcome people going into the public sphere to have them. Martha Beck has a book called Integrity. Um, and in it she points out that the word integrity comes from integer, intact, and when we’re out of alignment with ourselves, that it can make us ill, like physically unwell, psychologically unwell. It’s it’s not it’s not good for us to behave pragmatically but immorally. In the psychotherapy world, it’s called incongruence. In the person-centered school of psychotherapy, it’s thought you can develop an incongruence, a sense of so one example might be you kind of live your life for other people. So your parents really want you to be a lawyer. In your heart of hearts, you think perhaps you’d much rather be a doctor, but you become a lawyer because that’s what your parents want. In the short term, that works because you get your parents’ approval and they’ll pay for your school. But in the long term, that incongruence can eat away at you and make life very difficult. You’re kind of living a double life. You’ve got your outer life, which you construct for other people, and you’ve got your inner life, which you sequester and you don’t express. And that sequestering produces a lot of shame, actually. Often that shame can be unconscious and psychologically detrimental. So absolutely, I think integrity, that sense of I am who I say I am, and I’m going to try and make my life a reflection of my real values, I think is super important. Yeah, absolutely. Looking for looking for congruence seems to be the work of midlife a lot of the time, right? My experience is getting into your 40s, you begin to do a bit more of the serious inner work. Perhaps I’m late to late to the party. Uh when you mentioned the lack of religion, that’s I think fascinating and probably a whole other conversation. But I think the way we look at tech is in some sense religious, it’s deified. We’re looking at it to save us. And you think of what will make us happy through convenience or prolonging our life. And it’s not like you get rid of religion and you get rid of the religious urge. All the stuff that was embodied in religious practice still needs a home, and there are better and worse homes for it. Yeah, I mean, absolutely. The religious whole. So, like, what is that religious whole? It’s a it’s a craving for a life that has meaning, a life that makes sense in kind of a grand narrative, a sense that one’s life is important, a sense that one’s actions and choices are important and have consequence. And I think that kind of deification of technology is one of many things which go into that god-shaped hole. There’s the technological stuff, consumerism, materialism, nihilism, cynicism, hedonism, all of these things could take over someone’s life in the absence of a grander meaning. And I think that’s a huge problem. Going back to hunter-gatherer ancestors, the hunter-gatherer tribes were pretty exclusively religious. Now we live in a society that’s increasingly secular, but people are religious about all sorts of things. People are religious about stacking wealth, people are religious about their politics, people are religious about their nutrition, and it’s quite people are religious about atheism. It’s kind of funny to see in some sense. It’s interesting. I think we’re seeing a resurgence of interest in religion, at least statistically, and who knows if it’s just this year or the last few years, a sense that there’s a returning to older ways. Interestingly, within Christianity, it’s the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches that are growing. The ones that are highly ritualistic and structured and mystical, a sense of wonder to them as well. So I I wonder that we’ve kind of explored the second part of your question, but maybe we could bring it into explicit conversations. How do we prepare for an increasingly unpredictable future, given the fact that technology, as you say, has eroded our sense of agency and confidence, made us intolerant of uncertainty, desensitized to joy and experience, and eroded those social skills which are so central to human flourishing? How do we prepare for a future which seems to be getting more technologically advanced? More of the the kind of the work of being a human is is being given over to large language models and things like that. Maybe you could start with that personally. How do you prepare for it, Alex? Yeah, and and to so to frame this, uh my line of thinking is something like in a world with a lot of technology and a lot of unpredictability, there’s going to be A things you can’t control, as we’ve already discussed, and be a lot of options like technology and a technological world actually produces a lot of options. In a world like this, I think something like self-development is moving from I think in the past where there’s a bit more optional, a bit more of a luxury. Like you could use self-development to make the most of your potential. But if you think of living in the 1950s or the 1960s, you had a lot less options of how to live life. And so I think in those times self-development still mattered, but less. If you’re around in the UK in the 1950s, had a lot less choices in terms of your career, you had a lot less choices in terms of like how you’re going to set up your life, you’re probably going to get married, you’re probably going to have children, there’s a good chance you’re going to be religious. Almost anything is on the table. And so I think self-development is less a luxury and more kind of mandatory. A lot of my answers are going to be around stuff that’s been around in the self-development world for a long time. Two caveats. One, there are no guarantees. I really don’t know what the future is going to hold. I’m doing my best to give educated guesses as to what I think would be useful. And then the second caveat is I I’m not wanting listeners to come away with the idea that I have accomplished all of these things. I am very much a work in progress. Like everyone else. But the kinds of things I’ve been thinking about how to prepare for a future. Firstly, I think certain cognitive skills. I think the ability to delay gratification is super important. The ability to push through discomfort to get a greater reward in the future. That could be in work, it could be in financial investing, it could be in a variety of contexts, but basically that meta-skill of I can be uncomfortable now for a reward later. The second one I would like to mention is focus. This focus obviously relates to delay gratification, but the ability to focus on something both in the short term enough to get a given task done, but also focus on the medium to long term. I’ve decided I’m going to start my podcast project. I’m going to give it the focus it deserves. I’m going to make at least my first six episodes or ten episodes before I do anything else. Because without focus and doing something for a reasonably long period of time, you don’t really know where you’re at. You haven’t really built anything. I think developing character and integrity, we’ve already discussed, is going to be super important. Foundational aspects of character like honesty, reliability, meaning what you say, saying what you mean. I even think trying to build a life that you like, that you actually on some level enjoy or are aligned with is kind of a moral question. And that may sound odd, but I think it’s a moral question because if you really dislike life, you tend to become very resentful towards yourself and the people around you. And that tends to have negative consequences. So that’s a little bit of morality and character building. I think taking care of your physical body is going to be super important in the technological state we’re in now. People have to be a lot more proactive to be physically strong. Because people don’t naturally lift things or walk long distances, we get frailer. I think this is only going to continue to be the case. So we have to make proactive efforts to remain physically strong through exercise, nutrition. We have to be very, very proactive about limiting the foods that we eat that we know are basically junk, and very proactive about eating foods which we know really nourish us. This wasn’t the case for most of human history. The food you were given was food that was healthy. It’s not the case now. Increasingly, it’s not going to be the case in the future. I think being proactive about developing social skills. For most of human history, you lived in and amongst your family and close friends and associates. That’s how we lived forever. Now socializing has become this kind of add-on luxury. Oh, I’m going to make an effort to socialize this week. Why are you going to make an effort to socialize? Because actually, I work from home and I can just get food delivered to me and I can just watch Netflix. I think a person should be really proactive about developing social skills, the art of expressing oneself, the art of understanding where another person is coming from, the art of having fun with someone and just relaxing, which doesn’t sound like it should be a set of skills, but it kind of is because it’s the skill of letting go and letting yourself relax with another person. The art of persuasion or of developing a vision and getting people on board with that vision for a team or a project. I think quite a lot about career, and you know, one concern is AI taking our jobs or making our careers a lot more fragile. From the career sphere, I think a lot about developing cross-sections of different skills which are uncommon because that makes you ever more unique in the job market. So, for example, if you are looking at my case as an example, if you’re a psychiatrist, you’re kind of one among you know thousands to millions. But if you’re a psychiatrist and also a psychotherapist, immediately you’re part of a smaller group. You’re a psychiatrist, psychotherapist podcaster. Now maybe I’m like one of ten people at a certain level. I really encourage people when they’re thinking about their careers to find sets of skills which are really disparate and see if you can combine them. In those combinations, you’re immediately going to be much more singular for career planning. Try and get really good at something that humans appreciate from humans as opposed to from something else. I don’t think when a company is balancing their books, they particularly care if their accountant is human or not. If an AI can deliver the results, you’re going to go with the AI accountant, probably. But something like a therapist, there’s almost always going to be humans who want a therapist that’s also human. Or public speaker, for example. I can’t imagine it’s going to be particularly enjoyable to watch an AI software speak about life. If you want to hear someone speak about life, you probably want to hear it from a human. Those are a couple of examples. The last bigger category is financial, actually, money. Very practical stuff. I think money is super important, probably in a lot of self-development circles. We live in a very consumerist society. I think what defines consumerism is not just consuming anything, it’s consuming luxuries, like things you don’t particularly need, and becoming an ingrained habit, and you feeling like something really important is being taken away if you can’t have a particular luxury. So increasingly, I’m thinking about the importance of proactively, again, not because you have some big financial problem now, but proactively relying a lot less on luxuries, saving money, investing money in low-risk diversified assets, so that you’re much less vulnerable to economic changes, which are just really unpredictable, very difficult to anticipate. I think it’s a good rule of thumb that the more cash and assets you have, probably the better, and the more reliant you are on modern luxuries and conveniences that you don’t, strictly speaking, need. I think you’re in a more vulnerable position. So those are the few you know things I’ve been thinking about, and I’m applying most of these to my own life. We can dive deeper into any of them if you like. Alex, that’s it’s so so helpful. So you mean eight things, and they’re all they’re all incredibly rich. The financial one, it just just because uh the last thing you mentioned, and it’s slightly different from the others, in as much as it’s not that you want more money so you can accrue more stuff and you know go go on bigger holidays or buy bigger yachts or whatever. It is because you there’s baseline needs, and without those, you can’t you can’t essentially you can’t flourish. Beyond those baseline needs, wealth doesn’t add a great deal to our well-being. You just want to be financially resilient. Is that is that where you can make it? Yeah, it’s definitely about being financially resilient and realizing that wealth is not sufficient for happiness and can in some ways be detrimental to happiness. I do think enough wealth is a prerequisite. If you don’t have enough wealth to meet your basic needs and maybe a little bit extra, it’s very unlikely that you’re gonna achieve a reasonable amount of psychological stability. And that’s why it’s so important. My focus on financials is not about accruing wealth and having a lavish lifestyle, it’s about being resilient, particularly when random economic changes, recessions, depressions, changes in the housing market, changes in the job market could occur. Uh-uh, and we don’t know what’s going to happen. I think that’s really important. Yeah, these other points you mentioned are really interesting. They bring to mind um a quote that I will butcher from Wendell Berry. He said, The division in the future will be between those who want to live as creatures and those who want to live as machines, which I love. I think it’s prescient as well. Lots of what you’re saying are they kind of humanizing qualities, the things that often make us feel more alive, being embodied, developing social skills. There one way you might think of this constellation of things to lean into are what are the more humanizing aspects of life and how do you lean into them and away from mechanistic simulacrum that is enveloping so much of our lives? Or at least use the technologies in a way that helps you and maybe elevates you rather than you just purely relying on it uh unilaterally, you know. So an example might be ChatGPT. What’s so revolutionary about ChatGPT? I mean, there’s tons of stuff that’s revolutionary, but one thing is that for the first time we have a technology that can think for us, and gosh, isn’t that amazing? But gosh, isn’t that also terrifying? There’s a wonderful article that came out recently in The Guardian called Are We in the Golden Age of Stupidity? And it’s primarily about Chat GPT and other technologies allowing people to outsource their thinking and reasoning. Is that going to impact people’s intelligence, intellectual functions, ability to reason? My opinion is almost certainly it will because we know. So in biology, there’s a saying use it or lose it, use a muscle or it will atrophy. I doubt that our intellect, cognitive capacities, our reasoning is going to be an exception. So taking ChatGPT as an example, you can use ChatGPT if you’re a writer to elevate your writing, to make it better, and in some sense to make it easier without necessarily wholesale outsourcing your writing to ChatGPT. But you can also just outsource it to Chat GPT, and you’re you’re no longer a writer at that point. If you were a writer before, your ability to write and think is going to atrophy and stagnate. So that there’s definitely a way of using these technologies that’s helpful, and it may be mandatory at some point in the sense that a person may not be able to compete in the marketplace if they don’t use certain technologies. If you’re a podcaster, for example, and you refuse to do remote interviews, it puts you at a real disadvantage because it means you have to only find people who live locally that you can interview in person. Whereas if you’re able to do a remote interview like we’re doing right now, that opens up a lot of possibilities. So that you use the technology rather than the other way around is going to be very important. I’m a big fan of the way the Amish community deals with technology. They have a trial group where they test it out for a number of weeks or months and they think, is this going to be good for us individuals and our collective lives? If so, bring it in. And obviously, people will vary in terms of what they think is helpful and what they think isn’t. But one of the points I think is helpful when thinking about people like the Amish is they do so in community. This list of things that you’ve given are fantastic, but I would find them hard to operationalize on my own, I think, if I was an isolated individual. So what does anything come to you when you think of what are the ways I can ensure these are embedded in my life? You know, joining communities, that kind of thing. Yeah, I’m absolutely, and I I think you’re right to point that out. I think it’s incredibly difficult to pursue a lot of these things by oneself. A lot of people, when they go down a more self-development path, they find themselves quite alienated from their family and friends. One thing that’s on my list in terms of physical health is not drinking alcohol and not using drugs. If the world goes to shit, uh I don’t want to be reliant on drugs and alcohol. I want my brain to be as strong as possible. Alcohol is really bad for our brain, so you might decide because the next 10 to 30 years might be really unpredictable, I just don’t want to drink, so my brain works really well. Doing that can be very alienating to a lot of people who are quite happy with the status quo. And so I think as much as is possible, I think it’s good to surround yourself with people who are like-minded. So if you’re interested in this kind of self-development stuff, finding people again, IRL, who are also into it, I think is a really good idea. I think podcasts have really helped because, at the very least, you can have a helpful voice in your ear. I know there are people who think the same way as you, face similar problems, and can help you out. But I don’t think there’s going to be a substitute for having people in your life who share your values, who want to save financially sustainably for the future. Or other people who want to pursue uncomfortable things, who want to train themselves physically, who also are interested in learning new skills to safeguard their career prospects. Having people around that have those shared goals and values, there is no substitute for that. I think to the extent that you can do it alone, that’s great, but definitely get help and find some sort of community. It’s really helpful. Alice, can I ask you, if as you think about this question and an unpredictable future, do you feel optimistic? Pessimistic? Somewhere in the middle? It depends on the time of day. I vary a lot. It’s easy to feel pessimistic, and it’s also easy to feel optimistic that I think is the nature of unpredictability. We don’t really know what’s going to happen. I think going back to this idea of confidence, what makes me cautiously optimistic is that I am being proactive in a lot of these different areas I’ve talked about, and that I’m making myself used to encountering difficulty and overcoming it. So that when some big difficulty might happen down the line, and big difficulties have always been a huge part of life, not just because of technology, you know, death, illness, war, what have you. I’m gonna feel a little bit more confident that I’m gonna be able to handle it. So again, I guess what I’m trying to say is to anyone listening, don’t rely on the news to make you feel optimistic or pessimistic. Because some days there’s gonna be some good stories, many, many days there’s gonna be terrible stories. Try and see if you can link your feeling of optimism and pessimism to the things you actually do proactively and the things which are in your control, because I think that’s that’ll ground you better psychologically. Excellent. Well, it’s it’s been super helpful actually for me hearing these things. I take one of the big things you’re saying is that we need to take life from the abstract realm of our thoughts into the real world, it’s there in that testing ground that we become better versions of ourselves, the kind of people we need to be in the future for ourselves and those around us. Honestly, like if you don’t, if you don’t want to take any of this detailed advice we’ve talked about, like just do stuff, just like find something to do. Again, that’s how I built my career. Find something interesting to do and just do it, even if it’s simple, even if the plan isn’t very good, even if um someone might make fun of you, find something to do which you find kind of inherently interesting, and make it happen in some concrete way. Maybe that’s writing if you’ve always wanted to write, maybe that’s acting if you’ve always wanted to act, maybe that’s starting your own business in the smallest possible way. Just bring something into reality because that is one of the most human attributes. We can imagine something and we can make it real. It takes time, we have to fail a lot, but we can do it. The problem is a lot of people get stuck in imagination and fantasy, and they never make that switch to I’m actually gonna make something happen. So if there’s one piece of advice someone could walk away with, it’s just make something happen in a small way, in a humble way, but guided by your interest. And if you do that a lot over many years, good things will happen. Fantastic. I think the implicit message that you’ve experienced and I’ve experienced in the podcasting is just being creative. There’s something about the human spirit that is indefatigably creative, but it needs to be given oxygen, it needs to bring things into incarnate them, you know. Absolutely. Alex, for listeners of the Examined Life, where can they go to find out more about your work? You’ve got you’ve got TED Talk, which which I thought was excellent. Actually, I do recommend people looking up Alex Kermi’s TED Talk, but where else? Yes, the best place to find me is the Thinking Mind podcast, which you can find out on YouTube, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, anywhere you get your podcasts, and that’s where that comes out once a week. And that’s where you’re gonna find anything I’m thinking about, writing about, interviewing expert guests once a month on the podcast. We are now looking at films, so I’m calling that thinking films. Up until this point, I’ve analyzed psychologically the movie Her, the Joaquin Phoenix movie from 2013, The Wolf of Wall Street, the Leonardo DiCaprio movie. This month it’s probably gonna be the Truman Show, or maybe Phantom Thread. I haven’t decided yet. So that’s something I’m excited about. Or also, we’re on social media, so it’s like Thinking Mind Pod on X and Thinking Mind Podcast on Instagram, uh, and we update there regularly. Thank you so much. That’s really helpful. Alex, thank you so much for your time and your expertise. It’s been such a pleasure chatting to you. Thanks, Kenneth. I appreciate it. Thank you for the invite.